Quantum Computing Breakthroughs That Changed Science in 2026

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Introduction: The Year Quantum Got Real

For years, quantum computing has lived in two worlds at once. In research labs, it has been a field of deep physics, delicate hardware, and incremental progress. In headlines, it has often been framed as a looming revolution that would upend cryptography, medicine, and artificial intelligence overnight.

In 2026, those two worlds moved closer together.

This was the year when several long-running research threads matured at the same time. Hardware became more stable. Control systems became more scalable. Networks moved beyond lab benches into city infrastructure. And algorithmic work began cutting the cost of real quantum computations.

Taken together, these breakthroughs did not mean that fully fault-tolerant, million-qubit quantum computers suddenly arrived. But they did mark a clear shift: quantum computing began to look less like a distant scientific ambition and more like an emerging layer of real computing infrastructure.

Below are the breakthroughs that defined 2026 — and why they mattered for science.

1. Majorana Qubits Move From Theory to Measurable Reality

One of the most closely watched developments in quantum hardware has been the quest for Majorana-based qubits. In 2026, researchers demonstrated a reliable way to read out information stored in systems consistent with Majorana zero modes — a key technical milestone for topological quantum computing.

The work builds on decades of theoretical research into particles first predicted by Italian physicist Ettore Majorana. In certain solid-state systems, quasiparticles can emerge that behave like Majorana fermions. What makes them so compelling for quantum computing is how they store information.

Instead of encoding quantum information in a single physical location, Majorana-based qubits distribute it non-locally across paired states. That structure makes them inherently more resistant to certain types of environmental noise. In theory, this could dramatically reduce the overhead required for error correction.

In 2026, researchers refined techniques such as quantum capacitance measurements to detect the even-odd parity states associated with these quasiparticles. In simple terms, they found more reliable ways to read whether a topological qubit was in one state or another without destroying the fragile quantum information.

Why does that matter?

Because reading a qubit without collapsing or corrupting it is one of the central challenges in quantum engineering. Superconducting and trapped-ion systems have made huge strides, but they still require heavy error-correction layers. If topological qubits can reduce that burden at the hardware level, they could fundamentally change how large-scale quantum systems are designed.

For science, the implications are significant. More stable qubits mean longer computations. Longer computations mean deeper simulations in chemistry, condensed matter physics, and high-energy models that are currently intractable.

The 2026 results did not prove that fully topological quantum computers are ready for commercialization. But they provided some of the clearest experimental validation yet that this path is viable.

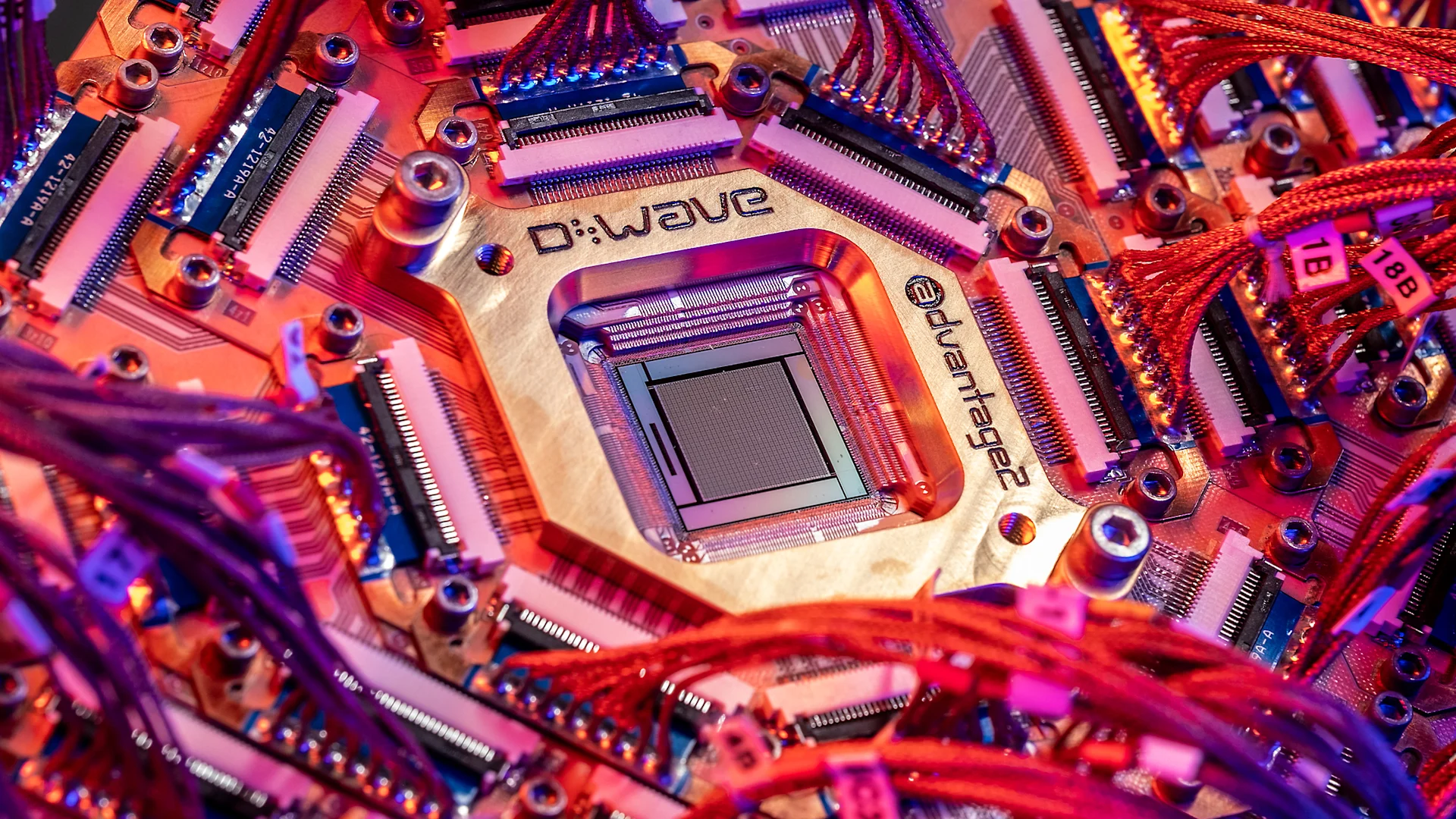

2. D-Wave’s Scalable Control Architecture

In early 2026, D-Wave Systems announced a major advance in scalable control technology for quantum processors. While D-Wave is best known for quantum annealing systems, this milestone focused on a deeper hardware bottleneck: wiring and control.

Traditional quantum processors require extensive external control electronics. Each qubit often needs its own dedicated control lines. As systems scale from dozens to hundreds or thousands of qubits, the number of wires and connections becomes physically unmanageable. Cryogenic systems add another layer of complexity, since most superconducting qubits operate near absolute zero.

D-Wave’s 2026 development integrated more control logic directly onto cryogenic chips. Instead of routing thousands of signals from room temperature electronics down into dilution refrigerators, the architecture allowed local signal generation and multiplexing at low temperatures.

That may sound like a niche engineering improvement. It is not.

Scalability is the defining challenge of quantum computing. Adding qubits is easy on a whiteboard. Adding them in a lab, without exponentially increasing error rates and hardware complexity, is extremely difficult.

By reducing wiring overhead and improving control density, D-Wave’s approach addressed one of the least glamorous but most consequential barriers to growth. It also signaled a broader industry shift: companies are no longer focused only on increasing qubit counts. They are investing in full-stack engineering — from cryogenics to firmware to hybrid cloud integration.

For scientific computing, scalable control means researchers can realistically plan for experiments that require hundreds or thousands of interacting qubits. That opens doors to larger combinatorial optimization problems and richer physical simulations.

3. A Real Quantum Network in New York

In February 2026, Cisco and Qunnect demonstrated a metropolitan quantum network across parts of New York City. The system transmitted entangled photons over existing fiber-optic infrastructure between Manhattan and Brooklyn.

This was more than a lab experiment.

Previous quantum communication tests often relied on short distances, highly controlled environments, or specialized infrastructure. The New York deployment showed that quantum signals could be integrated into real telecom fibers running through a dense urban environment.

The system maintained entanglement across roughly 17 kilometers, using centralized cryogenic equipment while keeping many endpoints at room temperature. That architectural choice matters. If every node in a quantum network required complex cooling hardware, scaling it would be impractical.

Why is quantum networking important for science?

First, it enables distributed quantum computing. Instead of building a single monolithic processor, multiple smaller quantum devices can be linked through entanglement, sharing quantum states across distances.

Second, it underpins quantum-secure communication. Entanglement-based protocols allow detection of eavesdropping, making them attractive for critical infrastructure and financial systems.

Third, quantum networks enable new forms of sensing. Entangled systems can enhance precision measurements in fields ranging from astronomy to geophysics.

The 2026 New York demonstration did not create a global quantum internet. But it proved that quantum networking can leave the laboratory and coexist with real-world telecom systems. That is a meaningful shift from theory to infrastructure.

4. Algorithmic Efficiency: Cutting the Cost of Quantum Computation

Hardware improvements tend to get the headlines. But 2026 also brought major advances on the software side.

One of the biggest cost drivers in fault-tolerant quantum computing is the use of non-Clifford gates, such as T gates, which require resource-intensive error-correction procedures known as magic state distillation. In many algorithms, these operations dominate the overall computational cost.

In 2026, researchers published new techniques to reduce the number of required non-Clifford operations in certain classes of algorithms, particularly in simulation and optimization tasks. By restructuring circuits and exploiting problem symmetries, they were able to lower resource requirements without sacrificing accuracy.

This kind of work does not change the laws of physics. But it changes feasibility.

If an algorithm requires 10 million expensive operations, it may be unrealistic on near-term hardware. If clever compilation and circuit design reduce that to 1 million, it suddenly becomes plausible.

Algorithmic efficiency is especially critical during the current “pre-fault-tolerant” era. Most quantum systems today operate in a noisy regime. Hybrid workflows — where classical computers handle part of the workload and quantum processors tackle the hardest subroutines — are increasingly common.

By lowering gate counts and circuit depth, 2026’s algorithmic breakthroughs made hybrid models more powerful. Researchers in chemistry and materials science can now design experiments that were previously considered too resource-heavy.

In short, smarter math made limited hardware more useful.

5. Larger Qubit Arrays and Progress in Error Correction

Scaling qubit counts has been a central metric of progress in quantum computing. But raw numbers are misleading if error rates grow alongside them.

In 2026, multiple research groups and companies reported progress not just in increasing qubit arrays, but in reducing logical error rates as systems scaled. This is a critical distinction.

Physical qubits are noisy. Logical qubits — built from many physical qubits using error-correcting codes — are the true building blocks of reliable quantum computation. Achieving a regime where adding more physical qubits actually reduces the error rate of logical qubits is known as crossing the fault-tolerance threshold.

While fully fault-tolerant systems remain under development, 2026 saw strong experimental evidence that certain architectures are approaching this threshold. Surface codes, lattice-based error correction, and improved calibration techniques have all contributed.

For science, this progress changes the conversation. Instead of asking whether long computations are possible in principle, researchers can start estimating when they will be practical.

Accurate quantum simulations of complex molecules, nuclear interactions, or exotic materials require deep circuits. Without error correction, those circuits fail before completion. With improving logical stability, the horizon for meaningful simulations moves closer.

The breakthroughs of 2026 did not eliminate noise. But they narrowed the gap between experimental prototypes and scientifically reliable machines.

6. Hybrid Quantum-Classical Workflows Become Standard Practice

Perhaps the most important shift in 2026 was philosophical rather than technical.

Instead of waiting for perfect, fully fault-tolerant quantum computers, researchers embraced hybrid models as a practical bridge. In these workflows, classical supercomputers handle data preparation, optimization loops, and error mitigation, while quantum processors perform specialized subroutines that benefit from quantum effects.

This approach has shown promise in:

-

Molecular energy estimation in quantum chemistry

-

Combinatorial optimization in logistics and finance

-

Materials design for batteries and superconductors

Hybrid systems acknowledge reality. Current quantum devices are powerful but limited. By integrating them into classical pipelines, scientists can extract value today rather than a decade from now.

Cloud platforms have played a major role in this shift. Quantum hardware is increasingly accessed remotely, allowing research teams worldwide to experiment without building their own cryogenic labs.

In 2026, hybrid quantum-classical computing stopped being a workaround and became the default strategy. It reframed quantum machines not as replacements for classical computers, but as accelerators — similar to how GPUs transformed machine learning.

Conclusion: Why 2026 Marks a Turning Point

Quantum computing did not “arrive” in 2026 in the way science fiction once imagined. There was no overnight collapse of encryption or instant solution to unsolved mathematical problems.

What happened instead was more meaningful.

-

Majorana-based systems demonstrated clearer experimental control.

-

Scalable hardware architectures addressed engineering bottlenecks.

-

Metropolitan quantum networks proved compatibility with real infrastructure.

-

Algorithmic research reduced resource costs.

-

Error-correction experiments moved closer to fault tolerance.

-

Hybrid workflows matured into practical tools.

Each breakthrough addressed a different layer of the quantum stack — physics, hardware, networking, software, and systems integration.

Together, they changed the trajectory of the field. Quantum computing is no longer defined only by how many qubits a chip contains. It is defined by how well those qubits are controlled, corrected, connected, and integrated into broader scientific workflows.

Looking back, 2026 will likely be remembered not as the year quantum computing finished its journey, but as the year it clearly moved from promise toward practice.

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

.png)